Well, it feels that spring has finally sprung and whilst I welcome the sunshine and a chance to warm myself like a lizard in the sun, ladies of previous centuries would have been aghast at the very thought.

During the 19th century women, especially those of the upper classes, actively sought a pale complexion. Such a pallor distinguished them from those that laboured outdoors, reinforcing status and visually portraying their position as a woman of genteel inactivity, a women of class. As such protection of the skin from the sun was of vital importance and so the parasol was an essential and stylish accessory.

In recent months I’ve had the pleasure of archiving two beautiful late 19th century parasols. The first a striking ‘Carriage Parasol’ of cream silk and black lace (c. 1860-1880). The design of this parasol is ingenious, halfway down the stick, the parasol has a hinge allowing it to be neatly folded into a more manageable size. Carriage parasols came into use in the early nineteenth century and were made popular by Queen Victorian in the 1840s as she enjoyed parading in an open carriage.

Children were also expected to protect their complexion and this little paisley parasol (c.1890s) made by W. & J. Sangster Umbrella Makers is a rather beautiful example. The canopy is of printed silk crepe, edged with cream fringing which rather wonderfully had little bits of grass, seeds and debris lodged in it (now delicately removed). Whilst little girls were expected to be little women, clearly this child had space to play and enjoy the outdoors. The intricate paisley pattern is based on a repeat of three large, clustered tear drops in blue, pink, green, burgundy and brown and printed onto a cream base. The ‘ferrule’, possibly ivory, has a loop to enable the child to carry it.

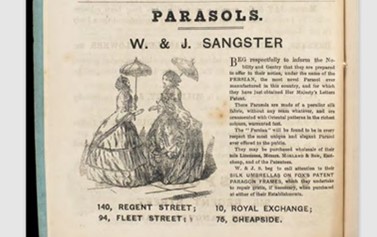

W. & J. Sangster Umbrella Makers were a prominent London based firm established in the late 18th century, initially a walking stick and cane makers they later expanded into umbrellas, parasols and sunshades in the early 19th century. Their advertising can be found in numerous publications; interestingly these adverts not only tell us about fashions of the day but give indications of an ever expanding trade and industry network alongside a glimpse into attitudes regarding an expanding world and the availability of the new, novel and strange.

Image from Dickens, C.; Little Dorrit, (London: Charles Bradbury & Evans, London. 1856) June VII, pp. 12.